The artist (or film director) observes the world, filters his observations through his unique way of looking at things, and then expresses his thoughts and feelings by creating art.

Pablo Picasso’s famous mural Guernica, for example, is a raw and emotionally direct tribute to the Spanish town of Guernica, bombed during the Spanish Civil War. Picasso has taken a horrifying real life event and transformed that event into art.

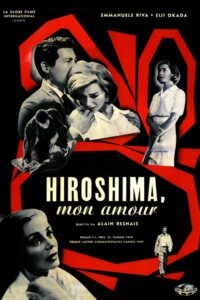

Similarly, the director of “Hiroshima mon amour,” Alain Resnais, takes the horror of the Hiroshima bombing and the horror of the punishment of collaborationism in post war France and transforms those events into “Hiroshima mon amour,” a cinematic masterpiece of the highest order. Ultimately, as I will argue in this essay, it is the work of art that gives meaning to the underlying real life events.

Here is the quietly revelatory note Bernard Hoffman wrote on September 3, 1945, to LIFE’s long-time picture editor, Wilson Hicks:

We saw Hiroshima today or what little is left of it. We were so shocked with what we saw that most of us felt like weeping; not out of sympathy for the Japanese but because we were revolted by this new and terrible form of destruction. Compared to Hiroshima, Berlin, Hamburg and Cologne are practically untouched. The sickly sweet smell of death is everywhere.

Shaved Woman of Chartres is an iconic black and white photograph taken by Robert Capa on August 16, 1944. A week after the liberation of Paris, women deemed collaborators with the Nazi regime, especially those who had been romantically or sexually involved with German men, were punished in France with head shaving. They were often paraded through the streets as a means of humiliation before being sent to jail.

The photograph shows one of these women, Simone Touseau, 23 years old, who had been a translator working for the Germans. She was in a relationship with a German soldier and bore him a daughter. The picture shows her being paraded through the streets of Chartres while carrying her infant daughter in her arms.

Simone’s head is shaved and her forehead has been branded by applying a red-hot iron as a sign of collaborationism. Her father walks ahead, carrying a bag, while her mother, who has suffered the same punishment, is walking in front of the father, and is partially covered by him. Simone is being escorted home from where she would go to jail.

Looking at Capa’s photograph, I am reminded of Emmanuelle Riva’s character in the haunting New Wave masterpiece “Hiroshima mon amour” directed by Alain Resnais. Riva’s character, at the tender age of eighteen, had also fallen in love with a German soldier, been discovered by her neighbors, and been humiliated and punished. In addition, her German lover is shot by a sniper and dies in her arms.

We meet Emmanuelle Riva’s character some years after these traumatic events. Her memories of these events are still raw. She cherishes the love she experienced, but she may also feel guilty for what happened. She also appears to feel that her punishment was unjust.

Hiroshima mon amour is a profound meditation on the horrors of war, on remembering, and on forgetting. The horrors of war are presented as both public horrors and private horrors. Similarly, remembering and forgetting are both public and private matters.

Regarding the present, the city of Hiroshima has been completely rebuilt only fifteen years after the city was destroyed by an atomic bomb. Tourists are visiting ground zero. A French actress (played by Emmanuelle Riva) is making a film “about peace.” A Japanese architect (played by Eiji Okada) has fallen in love with the actress.

Regarding the past, the traumas of the war in Europe and of the war in the Pacific are recent memories. The architect simply states that he was a soldier in the Japanese army. The actress tells her lover a more complicated story. She tells him about how her passionate love for a German soldier was discovered by the people in Nevers, her hometown in France. She was shamed, humiliated, and spat upon by her neighbors. Later, she is crippled by grief when her German lover is shot dead by a French sniper. Telling her story is a way of keeping her lover’s memory alive. After listening to her story, her Japanese lover tells her, “I know now that I shall think of this story as of the horror of forgetting.”

“In my film, time is shattered,” Resnais said. In “Hiroshima mon amour,” the storytelling is circular and inconclusive. Past, present, and future are entwined. To embrace the future, perhaps the past must be forgotten. The trauma of the past, however, leaves the future uncertain. Eric Rohmer, discussing Hiroshima mon amour, famously called this dilemma the “anguish of the future.”

Resnais uses images, sounds, and words to guide the viewer as he plays with time and location. Be sure to pay attention to the actors hands. In a particularly moving scene, the actress looks down on her sleeping Japanese lover. He opens and closes his hands while dreaming. The movement of his hands mirrors the opening and closing of her German lover’s hands after he is shot. The wonderful musical score by Georges Delerue and Giovanni Fusco announces whether we are witnessing events in Europe or Japan. Listen carefully to the music for cues regarding the location. The poetic script by Marguerite Duras manages to be both specific and universal.

Hiroshima mon amour is a very intimate film. It is immersive and dreamlike. The images in the film have a strange hypnotic quality. The film’s final lines suggest a story with no end. “Hiroshima. That’s your name,” she tells him. He replies, “It’s my name. Yes. Your name is Nevers. Nevers, a city in France.” Each character is forever located in the place from which they came. Each character reminds the other not to forget.