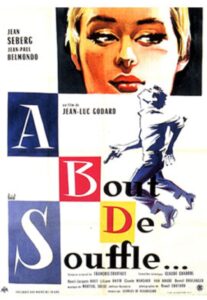

This movie poster advertising the French New Wave classic Breathless contains a spoiler. The poster shows that a character in the movie has been shot. Does this ruin the movie for you?

My daughter was a junior high-school student and a huge fan of the Harry Potter novels. She informed me that she had read each novel seven times! We were on our way to see the latest Harry Potter movie based on the novels. I asked my daughter why she needed to see the movie since she had already read the book. Her answer was instructive, “I want to see what everything looks like. I want to know whether the movie is different from the book.” It appeared that familiarity with the story hadn’t spoiled the movie for her. In fact, just the opposite had occured. Familiarity with the story had made her even more eager to see the movie!

In his book, The Films In My Life, the director Francois Truffaut puts it succinctly, “The scenario of a film is not the film.” Knowing details about the plot of a movie you are about to watch isn’t going to ruin the movie. On the contrary, I firmly believe that the more you know about a movie beforehand the more engaged with the movie you are likely to be and the more likely you are to enjoy the movie!

I learned about a study published in Applied Cognitive Psychology that supports my theory that “there is no such thing as a spoiler.” The authors of the study had people watch a suspenseful 30-minute TV episode directed by Alfred Hitchcock titled “Bang! You’re Dead.” The purpose was to determine the extent to which knowing the outcome of a dramatic scenario would affect a viewer’s ability to be drawn in by it.

Participants watched a short episode in which a young boy finds a loaded gun and mistakes it for a toy. The boy grabs it and walks around his small town pointing it and shooting at people and yelling “Bang! You’re dead!” oblivious to the fact that there is a bullet in the chamber.

Participants — a sample of undergraduate students — were told to raise their hand every time any character said the word “gun.” In the control group, participants knew nothing about how the story would end. As the suspense mounted midway through the show, they were so immersed in the events onscreen that they forgot all about their assignment.

In a different group, participants were told how the program would end. The authors of the study predicted that knowing the ending would lower their engagement — and allow them to better remember to respond to the word “gun.”

The authors of the study were wrong.

At the exact same point in the show participants neglected their assignment in a similar manner as those in the control group. In other words, they were just as immersed in the story even though they knew the outcome. In follow-up questionnaires, they also reported the same levels of engagement and enjoyment as those who didn’t know the ending.

The truth is, we are just as likely to get caught up in a story even when we know what is coming — perhaps because more significant factors determine our enjoyment of narratives rather than simply waiting to learn or guess their resolution. Humans are hard-wired not just to absorb facts but also to lose themselves in stories and attune themselves to the characters and plots unfolding on the screen.