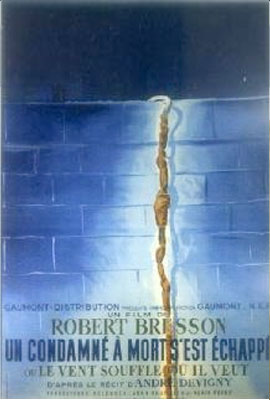

(1956)

directed by Robert Bresson

“A Man Escaped” is about a man condemned to death in Montluc, a Nazi prison camp in German-occupied France. The character of Fontaine, a captured resistance fighter, is based on the real life experiences of Andre Devigny who escaped from Montluc on the same day he was scheduled to die. The film is also informed by Bresson’s own experiences as a prisoner of war during World War II. Devigny assisted Bresson in the shooting of the movie. He rarely left the set because Bresson kept asking him to show his actor exactly how to use a spoon as a tool, how to write on the walls, how to camouflage his work, and how to tap out a message.

“A Man Escaped” is an unusually tactile film which consists almost entirely of closeups of objects and closeups of the man who manipulates the objects. It begins with a close-up of Fontaine’s hands while he is in transit to the prison. One hand moves toward the car’s door handle. When Fontaine exits the car, we hear gunshots but the camera’s gaze remains in the car. My nerves fray at the memory! Before we have even arrived at the prison, Bresson has focused our senses on the subtleties of space and sound.

Most of what happens in the movie takes place in Fontaine’s cell. We live with him in his prison cell. By looking intently at every detail, Fontaine devises a way to get through the cell’s door and then determines how to get over the prison walls. He solves the problems that keep cropping up with ingenuity and incredible focus. For the viewer, there is almost unbearable tension throughout the film.

We see what Fontaine sees. We hear what he hears. We watch Fontaine examine his cell. We are present when he discovers a way to escape. The sounds in the film have a hallucinatory quality, the sound of distant trains, the bolting of doors, the shuffling of boots, the tapping on a wall, the splintering of wood.

Fontaine’s conversations with a fellow prisoner through barred windows are reminiscent of a confession with a priest. In his indecision about when to make his escape, Fontaine experiences a lapse of faith. “A Man Escaped” is a deeply spiritual film about defiance, despair, hope, and faith in oneself and others.

Fontaine is forced to bring along a fellow prisoner. His alternative is to kill the other man. He demonstrates faith in a fellow human being and it turns out that he could not have escaped without the other man’s help. That it is possible to maintain one’s faith in humanity under such terrible conditions is an important part of the film’s message.

Robert Bresson

Robert Bresson, the director of “A Man Escaped,” is the most original of all the French New Wave directors. In her essay, “Spiritual Style in the Films of Robert Bresson,” Susan Sontag identifies the thoughtful, introverted quality that distinguishes Robert Bresson’s films. “The reason that Bresson is not generally ranked according to his merits,” writes Sontag, “is that the tradition to which his art belongs, the reflective or contemplative, is not well understood.”

Bresson’s films are radical in their understatement. He developed a new language for film which emphasized image and sound rather than straightforward storytelling. Bresson called his approach “Writing with images in movement and with sounds.” In his film “A Man Escaped,” we know the film’s outcome right from the beginning based on the film’s title. What is important is not the actual escape but the images and sounds that lead to the escape.

Bresson felt that sounds were often more important than images. “The noises,” he wrote, “must become music.” The soundtracks to Bresson’s films are just as important as the images. He emphasized the evocative qualities of sounds as compared to the specific qualities of images. Bresson explains the importance of sound in his films, “The ear is, in some sense, far more evocative and profound. The whistle of a train, for example, can call to mind the image of an entire station, sometimes of a precise station you know, sometimes of the atmosphere of a station, or of tracks with a stopped train. The possible evocations are innumerable.”

In “A Man Escaped,” Bresson uses sound to create images in our mind that we don’t see on the screen. The executions of prisoners are marked by the burst of a machine gun firing in the distance. We never witness the executions. Conversations with a prisoner in an adjoining cell are reduced to taps on a wall. Approaching guards are announced by the sound of their keys hitting the stair railings. Just like the prisoners, we hear but we can’t see. The drama is located within the viewer’s mind rather than within the images on the screen.

Bresson also had strict ideas regarding the role of acting in film. For Bresson, acting belonged in the theater. It did not belong in film. “In film, acting does away with even the semblance of real presence,” he asserted. Bresson employed “models” rather than actors. He wanted people who were free of the “self-awareness” that destroys the illusion of reality. His “models” repeated their lines and gestures until they became automatic. Bresson thought this automatic quality was similar to the way real people speak.

Bresson is a cinematic philosopher who asks the viewer to listen and to think while watching. Bresson once said, “Hide the ideas, but so that people find them. The most important idea will be the most hidden.” The first viewing of a Bresson film can be an uncomfortable experience. I have found subsequent viewings of his films to be deeply rewarding, however.