(2002)

directed by Alexander Payne

Jeanne Moreau, speaking of her time making “Jules and Jim,” that most evanescent of films, described the experience as being “light and grave.” There is something similarly “light and grave” about all of Alexander Payne’s films, including “Election,” “Citizen Ruth,” “Sideways,” and “Nebraska.” Payne’s film “About Schmidt” walks the same delicate line between “light and grave.” Sublimely funny and exquisitely sad, “About Schmidt” presents a weary melancholy leavened with keenly observed comedy. “About Schmidt” also delivers a sharply delineated portrait of the American midwest.

Warren Schmidt has no intellectual curiosity. To say he is unaware of the larger world is an understatement. He lives in a home filled with sets of collectors items, still in their original packaging, accumulated by Helen, his wife of forty-two years. After his retirement from an insurance company in Omaha, he returns to the office to see if he can answer any questions that hias replacement might have. Unfortunately, his replacement doesn’t have any questions and Schmidt is left wondering if he has contributed anything of importance to the company he has worked for his entire career.

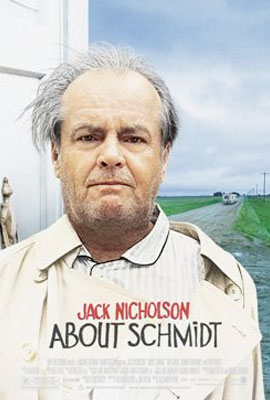

“The mass of men,” Thoreau famously observed, “lead lives of quiet desperation.” Schmidt is just such a man. Jack Nicholson, on the other hand, is known for his mischievous energy and determination to live life to the fullest. It is extremely entertaining to watch Nicholson play the role of Schmidt. Nicholson is the most watchable of actors and we are constantly amazed that he is able to perfectly portray the lifeless Schmidt. Nicholson discards all his usual mannerisms and manages to disappear into Schmidt’s character. Nicholson had said that his performance in “About Schmidt” is the most lacking in egotism of any of his film roles.

The opening scenes show Schmidt suffering through an excruciating retirement dinner. This sad affair mirrors the wedding reception at the end of the film. Speaking at the wedding reception, Schmidt is unable to voice his loathing for the man his daughter is about to marry and is overwhelmed with futility. He realizes that the cycle of empty striving and heartbreak is starting all over again.

After his retirement dinner, Schmidt is face to face with what remains of his life absent the structure and meaning provided by his job as an actuary for the Woodman Insurance Co. in Omaha, Nebraska. He barely knows the old woman he shares a home with. When Helen suddenly drops dead, Schmidt is astonished and bereft. He is not astonished at the enormity of his loss, however. Rather, he is astonished that he had so little to lose. I am reminded of the old man at the end of Ozu’s “Tokyo Story” who is also strangely unmoved by his elderly wife’s death.

Schmidt decides to hit the road in the Winnebago RV he and Helen had purchased for their retirement. This late in life road trip parallels Nicholson’s youthful odyssey in the classic road movie “Easy Rider.” Schmidt wants to visit his daughter in order to convince her not to marry a man he accurately perceives as an imbecile and a fraud. Schmidt’s potential new in-laws include Randall Hertzel (Dermot Mulroney), a water-bed salesman and promoter of pyramid schemes, and Randall’s mother Roberta (Kathy Bates), who embraces life with a new-age fervor. Schmidt finds himself enduring a sleepless night in an unfamiliar water bed and joined in a hot tub by the topless and terrifyingly rambunctious Roberta.

Responding to an advertisement for a children’s charity, Schmidt “adopts” a six-year-old Tanzanian boy named Ndugu. Encouraged to write to the boy, Schmidt pours out his feelings in long confessional letters. We can’t be sure whether or not he realizes that Ndugu probably can’t read or understand the letters. Certainly, though, there is no one in America who Schmidt would be able to open his heart to with such frankness.

In the last part of Schmidt’s journey, he runs into a couple in a camper from Wisconsin. A married woman, in a long conversation with Schmidt, comments on his sadness and anger. “I see inside of you a sad man,” she tells him. Later, when Schmidt receives his first letter from Tanzania, tears roll down Schmidt’s cheeks and the film comes to a tender and deeply satisfying conclusion.