(1931)

directed by Charlie Chaplin

Even before Chaplin began working on “City Lights,” the sound film was becoming dominant. Almost immediately, it was clear that audiences preferred films with sound. This posed a huge challenge for Chaplin. Chaplin’s Little Tramp character was known throughout the world. If the Little Tramp suddenly began to speak in English, that worldwide audience would suddenly shrink. Chaplin solved the problem by making “City Lights” as a silent film. Chaplin explained his decision as follows, “I was determined to continue making silent films. I was a pantomimist and in that medium I was unique and, without false modesty, a master.”

It is thought provoking to consider some of the advantages of silent film. Chaplin and the other silent filmmakers knew no national boundaries. Their films went everywhere without regard to language. There was no need for sub-titles. Children who see silent films don’t even notice that they’re “silent!”

Chaplin developed a passion for music as a child and taught himself to play the piano, violin, and cello. With the development of sound technology and beginning with “City Lights,” Chaplin composed musical scores for all his films. Because Chaplin could not read music, musical directors were employed to oversee the recording process.

“City Lights” tells the story of the Little Tramp’s love for a blind flower girl (played by Virginia Cherrill) and of his efforts to raise money for an operation to restore her sight. Of all Chaplin’s films, “City Lights” comes closest to representing all the different aspects of Chaplin’s genius. It contains the slapstick, the pathos, the pantomime, and, of course, it contains the Little Tramp.

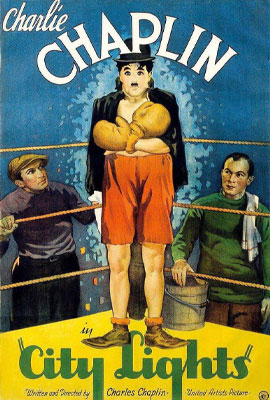

The movie includes some of Chaplin’s most famous comic sequences. There is the opening scene, where a statue is publicly unveiled only to find the Tramp asleep in the lap of a heroic Greco-Roman statue. When he tries to climb down, he gets his pants hooked on the statue’s sword, much to the amusement of the crowd which is present for the unveiling. There is also the famous boxing scene in which the Tramp uses his extraordinary footwork to always keep the referee between himself and his opponent.

In “City Lights,” the Tramp’s only friendships are with a drunken millionaire and with a blind flower girl. They accept him because they either don’t notice or can’t see his disheveled appearance. Otherwise, his appearance causes people to avoid him. Does the flower girl accept and treasure him only because she can’t see what he looks like? The last scene in “City Lights” answers this question in the most moving way imaginable.

After the flower girl’s sight is restored by an operation paid for by the Tramp, he wanders by her flower shop. Even though she can now see that he is a tramp, she smiles at him anyway and gives him a rose. Then, touching his hand, she suddenly recognizes him. “You?” she asks on the title card. He nods, tries to smile, and asks, “You can see now?” “Yes,” she says, “I can see now.” She sees and yet she still accepts him! The final scene of “City Lights” is famous as perhaps the highest moment in all of cinema. “City Lights” was Chaplin’s favorite of his films and remained so throughout his life.

Roger Ebert, the well known film critic, recounts one of his most treasured experiences as a moviegoer, “I was at the Venice Film Festival where all of Chaplin’s films were shown as part of the festival. One night the Piazza San Marco was darkened and “City Lights” was shown on a vast screen. When the flower girl recognized the Tramp, I heard much snuffling and blowing of noses around me. There wasn’t a dry eye in the piazza. Then complete darkness fell, and a spotlight singled out a balcony overlooking the square. Charlie Chaplin walked forward, and bowed. I have seldom heard such cheering.”

Charlie Chaplin

Charlie Chaplin, the director of “City Lights,” had a unique way of looking at the world. Shakespeare looked at the world and thought it resembled a stage. He said we are all merely players on that stage. Charlie Chaplin looked at the world and thought it resembled the life of a vagrant wandering the streets. The characters they created reflected their creators’ experience in the world.

Charlie Chaplin, abandoned by his alcoholic father, experienced the anguish of seeing his mother taken away to a mental asylum and experienced the terror of being picked up by the police. He was sent to a charity home at the age of seven. He was a nine year old vagrant hugging the walls of Kensington Road, as he recalls in his memoirs.

Chaplin did not attend school after the age of thirteen. From the age of fourteen, when his mother was committed to an asylum, Chaplin made his own way in the world. Of his childhood, Chaplin said, “I was hardly aware of a crisis because we lived in a continual crisis, and, being a boy, I dismissed our troubles with gracious forgetfulness.” This comment by Chaplin reveals a resilient and forgiving spirit.

Chaplin said his first influence was his mother, who entertained him as a child by sitting at the window and mimicking people passing by, “It was through watching her that I learned not only how to express emotions with my hands and face, but also how to observe and study people.”

The story of Chaplin’s life is one of the greatest rags to riches stories ever told. The film director Federico Fellini said, “Chaplin is a sort of Adam from whom we are all descended.” The film critic Andrew Sarris said, “Charlie Chaplin is arguably the single most important artist produced by the cinema, certainly its most extraordinary performer, and probably still its most universal icon.”

Six of Chaplin’s films have been selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the United States Library of Congress: The Immigrant (1917), The Kid (1921), The Gold Rush (1925), City Lights (1931), Modern Times (1936) and The Great Dictator (1940).

Chaplin explained how he selected the costume with which he became identified, “I wanted everything to be a contradiction, the pants baggy, the coat tight, the hat small and the shoes large. I added a small mustache, which, I reasoned, would add age without hiding my expression. I had no idea of the character. But the moment I was dressed, the clothes and the makeup made me feel the person he was. I began to know him, and by the time I walked on stage, he was born.”

All of Chaplin’s work revolves around the question of identity. He asks two crucial questions, “Who am I?” and “What is my place in the world?” Chaplin’s films follow the Tramp’s efforts to survive in a hostile world. The character lives in poverty and is frequently treated badly but remains optimistic. Defying his low social standing, he tries his best to be a gentleman.