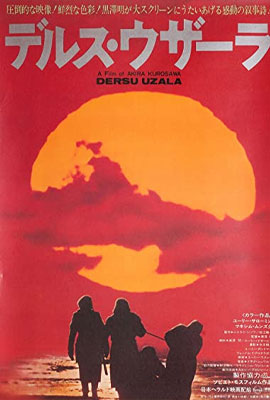

(1975)

directed by Akira Kurosawa

Kurosawa was at a low point in his career in the early 1970s. A crisis in the Japanese film industry had made financing his movies impossible. Kurosawa was also in constant pain from what turned out to be gallstones. As a result, Kurosawa attempted suicide. His film career resumed, however, when he received a Soviet invitation to direct “Dersu Uzala.” The film is based on a memoir of the same name by Vladimir Arsenyev, a book that Kurosawa had adored in his youth. Arsenyev was a Russian explorer who mapped much of the wilderness territory of the Russian Far East and studied its indigenous peoples in the early twentieth century.

“Dersu Uzala” is about the relationship between a well educated, sensitive European with connections to the urban world (the tall, handsome Yuri Solomin) and a nomadic, indigenous man in close touch with the natural world (the short, elderly Maxim Munzuk). The film is about the relationship between man and nature, about the deep friendship between two men of very different backgrounds, and about the difficulty of coping with the loss of one’s strength and ability that comes with old age.

“Dersu Uzala” is one of the most beautifully composed and photographed of Kurosawa’s films. Asakazu Nakai, the cinematographer for many of Kurosawa’s greatest works, captures the beauty of the wilderness landscape. He shot the film in widescreen to convey the vastness of the wilderness. Nakai’s camera is always at eye level. It is through the human eye that the vastness of the wilderness is viewed. Nakai’s use of color and light is masterly. The astonishing scene in which Dersu is forced to kill a Siberian tiger is breathtakingly beautiful. Later, Nakai uses an eerie red filter to capture the image of a vengeful spirit tiger.

It is Dersu’s small figure, however, that one remembers most after viewing the film. “Dersu Uzala” is a humanist masterpiece that is close in spirit to the films of John Ford and has many of the ingredients of a classic American western. In his 1991 study of Kurosawa, the American film critic, Stephen Prince, comments on Dersu’s unforgettable character:

“Dersu’s magnanimity is nourished by his perception of the essential spirituality of nature. He talks to the fire and to wind and water as if they were people. A soldier laughs and asks him why. Dersu replies that he does so because they are alive. Angry fire, water, and wind are frightening, he says. They are powerful men. A strong breeze suddenly appears, whipping leaves across the frame, as if in answer to his words. Earlier, in a magnificent image, Dersu and Arseniev stood on a vast plain, framed between the moon on their left and a fiery setting sun on their right, humans and celestial bodies alike flattened by the long lens into a single plane of space. It is an image of great mystery and serenity. As they contemplate the heavens, Dersu explains that the sun is the most important man because if he dies everything else dies, too. He initiates Arseniev into the secrets of the universe. Other Kurosawa heroes were in touch with important social and moral imperatives, but Dersu is connected to cosmic truths, and it is Arseniev’s blessing to have known him briefly.”

When Dersu begins to lose his keen eyesight and can no longer hunt productively, the captain invites him to stay at his home in the city of Khabarovsk. After inspecting his new home, Dersu asks, “How can men sit in a box?” He quickly discovers that he is not permitted to chop wood or to build a hut or fireplace in the city park. Despite his love for Arsenyev and Arsenyev’s family, Dersu realizes that his place is not in the city and asks Arsenyev if he can return to living in the wilderness. As a parting gift, Arsenyev gives Dersu a new rifle.

Some time later, Arsenyev receives a telegram informing him that the body of an indigenous man has been found with no identification on his body except for a card with Arsenyev’s name. Arsenyev is asked to come and identify the body. After Arsenyev arrives and explains his connection to the deceased man, the officer who found Dersu speculates that someone may have killed Dersu to obtain the new rifle that Arsenyev had given him. The most moving moment in the film is when Arseniev stands with his head bowed before his friend’s remains and with much love and respect simply murmurs his friend’s name, “Dersu…”

“Dersu Uzala” received the 1976 Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. It is included on the Vatican’s list of forty-five great films under the “Values” category, compiled in 1995 upon the 100th anniversary of cinema.

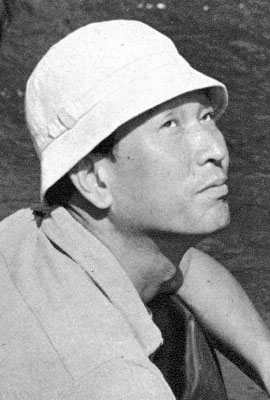

Akira Kurosawa

Akira Kurosawa, the director of “Dersu Uzala,” described his parents as being complete opposites. ‘‘My mother was a very gentle woman,’’ Mr. Kurosawa said, ‘‘But my father was quite severe.’’ Akira was the youngest of four sisters and four brothers. Akira was closest to his brother, Heigo, and shared his interest in art. Heigo, who was four years older than Akira, did not get along with their father and had moved out of the family home.

Without his father’s knowledge, Akira spent much of his time with Heigo during his teen-age years. What Akira remembered most about those years was going to the movies with his brother, who had taken a job as a benshi, or silent film narrator. ‘‘We would go to the movies, particularly silent movies, and then discuss them all day,’’ Mr. Kurosawa later wrote. ‘‘I began to love to read books, especially Dostoevsky, and I can remember when we went to see Abel Gance’s ‘La Roue’ and it was the first film that really influenced me and made me think of wanting to become a film director.”

When sound came to films, Heigo lost his job as a silent film narrator. Shortly thereafter, Heigo went on a trip to the mountains outside Tokyo and killed himself. ‘‘I clearly remember the day before he committed suicide,’’ Mr. Kurosawa wrote. ‘‘He had taken me to a movie in the Yamate district and afterward said that that was all for today, that I should go home. We parted at Shin Okubo station. He started up the stairs and I had started to walk off, then he stopped and called me back. He looked at me, looked into my eyes, and then we parted. I know now what he must have been feeling.”

Kurosawa’s films incorporate elements of Japanese art, including the subtlety of their feeling, the brilliance of their visual composition, and their treatment of samurai and other historic Japanese themes. What is most revolutionary, however, is the way they incorporate a Western appreciation for action and drama. With films like “Rashomon,” “Ikiru,” and “Throne of Blood,” Kurosawa changed the world’s perception of Japanese cinema.

“Rashomon” was shown at the Venice Film Festival in 1951 and was awarded the Grand Prix. It also won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. This was the first time a Japanese film had won such international acclaim, and Japanese films now attracted serious attention all over the world. “Rashomon” presented the same event as seen by different persons. This idea caught the imagination of audiences worldwide and advanced the idea of cinema as a means of delving into philosophical questions.

Kurosawa’s film “Ikiru” (“To Live”) is regarded by many critics as one of the finest works in the history of cinema. It concerns a governmental official with cancer who learns he has only six months to live. He seeks emotional support from his family but is disappointed. He tries seeking pleasure but is disillusioned. In the end, he is redeemed by using his position to help the poor.

Kurosawa’s film “Throne of Blood” was adapted from Shakespeare’s “Macbeth.” “Throne of Blood,” which reflects the style of the sets and acting of the Japanese Noh play and which does not use a single word of Shakespeare’s original text, has been called the best of all the countless films based on Shakespeare’s dramas.

Kurosawa rehearsed the scenes in his films meticulously then shot them from beginning to end using three cameras positioned at strategic points. “I put the A camera in the most orthodox positions, use the B camera for quick, decisive shots, and the C camera as a kind of guerrilla unit,” Kurosawa explained.

“The editing stage is really, for me, a breeze,” he said. “Every day, I edit the rushes together, so that by the time I am finished shooting, what is called the initial assembly is already completed. It’s not all that difficult. I just stay for maybe an hour or an hour and a half after everyone has left. That’s all it takes me.”

Kurosawa once described a trip he made with his brother, Heigo, through the ruins of Tokyo after the massive 1923 earthquake. More than 140,000 people died in the fires that followed the quake. As the pair moved through the ruins, his brother insisted that the young Akira look closely at the charred corpses.

“If you shut your eyes to a frightening sight, you end up being frightened,” Akira remembered Heigo telling him. “If you look at everything straight on, there is nothing to be afraid of.’’ Years later, Kurosawa said, “To be an artist means never to avert one’s eyes.”

Mr. Kurosawa once told the film scholar Donald Richie, “I suppose all of my films have a common theme. If I think about it, though, the only theme I can think of is really a question: Why can’t people be happier together?”