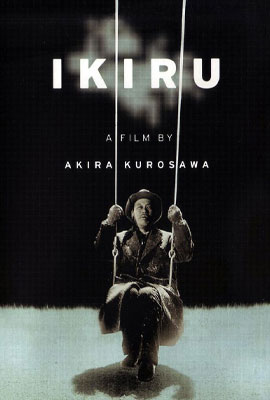

Ikiru (1952)

directed by Akira Kurosawa

Mr. Watanabe is a government bureaucrat who has worked for thirty years at Tokyo City Hall and never accomplished anything. He has risen to become chief of the section that handles citizen complaints. He sits with a pile of papers on his desk, in front of shelves filled with countless more papers, and shuffles the papers back and forth. Nothing is ever decided. In truth, his real job is to stamp each document to show that he has handled it. A narrator tells us, “This is the main character of our story, but it would be boring to talk about him now because he’s just passing the time, in fact, he’s barely alive.”

The film opens with a close-up of an X-Ray. As we gaze at the image, a narrator says in a matter-of-fact voice, “Symptoms of cancer are there, but he doesn’t yet know anything about it.” The X-ray fades into the sad, weary face of the actor Takasuri Shimura. Shimura plays an every man who embodies his character by not seeming to embody anyone at all. This is indeed a rare talent, because, if you think about it, most of us can’t help but embody a single, very specific, and typically uninteresting person, namely ourselves.

While Mr. Watanabe is waiting in the doctor’s office to hear his results, a fellow patient warns him that if the doctor prescribes specific dietary instructions, then everything will be fine, but if the prognosis is a “mild ulcer” with instructions that Watanabe can eat whatever he wants, then he has stomach cancer and maybe six months to live. When the physician begins to recite the patient’s warning verbatim, Watanabe knows his time is short. At home, he weeps in his bed and reflects on his life. The camera pans to a certificate on his wall praising him for twenty-five years of service at City Hall. This award is now a reminder of his wasted life.

After Mr. Watanabe learns he is dying of cancer, he tells a stranger in a bar that he has money to spend on “a really good time” but doesn’t know how to spend it. The stranger takes him out on the town, to gambling casinos, to dance halls, and to the red light district. They end up at a bar where the piano player is accepting requests and Mr. Watanabe, still wearing his overcoat and hat, requests the song “Life Is Brief.”

“Oh yeah, one of those old songs from the twenties,” the piano man says. But he goes ahead and plays it and the old man starts to sing ever so softly:

Life is brief,

Fall in love, maidens,

Before the crimson bloom fades from your lips,

Before the tides of passion cool within you,

For those of you who know no tomorrow,

Life is brief,

Fall in love, maidens,

Before your raven tresses begin to fade,

Before the flames in your hearts flicker and die

For those to whom today will never return.

Watanabe seems to recognize that it is not so bad that he must die. What is worse is that he has never lived. “I just can’t die. I don’t know what I’ve been living for all these years,” he says to the stranger in the bar. Usually, he never drinks, but now he is drinking with a vengeance, ignoring the pain in his stomach. He tells the stranger, “This expensive saki is a protest against my life up to now.”

Watanabe’s leave of absence from the office continues, day after day. Finally, a young woman, Toyo, who wants to resign, tracks him down to get his stamp on her papers. Watanabe is captivated by this lively girl from his office. He wants to understand what makes her so full of life. He admires her courage to leave her monotonous job and he befriends her, spoiling her with expensive meals and gifts. If only he can live like her, then he will have truly lived. At one point, however, Toyo asks him, “What help am I to you?” Mr. Watanabe’s answer is perplexing:

“You, just to look at you, makes me feel better. It warms this mummy’s heart of mine. And you’re so kind to me. No, that’s not it. You’re so young, so healthy. No, that’s not it, either. You’re so full of life. And me, I’m jealous of that. If I could be like you for just one day before I died. I won’t be able to die unless I can do that. I want to do something. Only you can show me. I don’t know what to do. I don’t know how. Maybe you don’t know either, but, please… if you can… show me how to be like you!”

Unfortunately, nothing is really special about Toyo’s life other than her youth. Toyo eventually becomes bored with their outings and accepts a job assembling children’s toys. During their final get together, she remarks that her new job makes her feel good because it makes her feel as if she is able to play with every baby in Japan. Watanabe is inspired by Toyo’s remarks and decides to try and make a contribution to the world in his remaining months.

In the first part of the film, we accompany Mr. Watanabe and look at the world from his perspective. In the second part of the film, our perspective shifts and we view the world from the point of view of his office colleagues and his relatives. After the interlude with Toyo, Kurosawa shifts the story to five months later. Mr. Watanabe has died. His actions during the last months of his life are revealed in a series of flashbacks as his office colleagues and his family members try to piece together his last few months.

The flashbacks reveal that Mr. Watanabe dedicated the last months of his life to helping some neighborhood women replace a puddle of sewer water with a new children’s park. He filed the correct paperwork and battled the never ending bureaucracy. In one of the most lyrical moments in all of cinema, Watanabe sits on a swing in the park he helped build, snow falling lightly around him, and quietly sings “Life Is Brief.”

Much of the discussion at Mr. Watanabe’s wake revolves around whether or not Mr. Watanabe knew that his condition was terminal. Inebriated and moved by the conversation, one person exclaims, “But any one of us could drop dead!” The implication is that Watanabe’s colleagues should walk away inspired, ready to use their status as public officials to help others. Of course, the next day at the office, Watanabe’s replacement in the role of Section Chief has learned nothing. He hands off a complaint to another department, avoids taking responsibility, and continues the cycle of bureaucracy.

By changing the film’s perspective, by showing the events of Mr. Watanabe’s final months from the point of view of his colleagues and family members following his death, Kurosawa has created a subtle work of art that inspires profound self-reflection. Kurosawa shows us just how subjective the events in our lives are when viewed from the outside. This helps us understand why one’s individual point of view is the only authentic vantage point from which to understand and judge one’s life. The sublime “Ikiru” is among the greatest, most life-affirming motion pictures ever made.