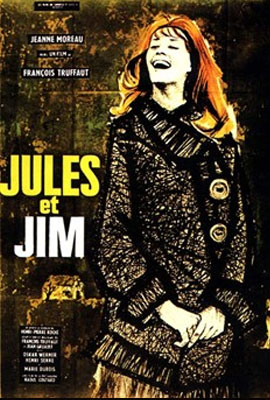

(1962)

directed by Francois Truffaut

Francois Truffaut, the writer and director of the film “Jules and Jim,” discovered Henri-Pierre Roche’s novel, “Jules and Jim,” among some second-hand books in a bin at a used bookstore. Truffaut explained that what caught his attention was the title of the book. “I was captivated immediately by the resonance of the two Js.” Describing his experience reading Roche’s novel, Truffaut said:

“When I read Jules and Jim, I had the feeling that I had before me an example of something the cinema had never managed to achieve, to show two men who love the same woman in such a way that the audience is unable to make an emotional choice between the characters because they are made to love all three of them equally. The book overwhelmed me. I resolved that if I should ever succeed in making films, I would make Jules and Jim.”

I think we can all agree that relationships are often fraught. In Bergman’s “Summer With Monika,” for example, we are confronted with Monika and Harrys’ separate hopes and dreams and disappointments. We are also contending with the expectations of society with regard to making a living, marriage, and raising a child. By adding another person to this combustible mix, the complexities increase exponentially. It is helpful, however, when taking a close look at a topic like “relationships” to explore the extremes. Truffaut was a very brave man to undertake such a project. That he created the masterpiece “Jules and Jim” while still in his twenties is a testament to his courage and creative spirit. Truffaut writes of the challenges of making Jules and Jim:

“I shan’t describe the atmosphere of anxiety and exaltation which surrounded the filming of Jules and Jim. I shall only say that Jeanne Moreau gave me courage every time I was overcome by doubt. Her qualities as an actress and as a woman made Catherine real before our very eyes, plausible, crazy, abusive, passionate, but above all adorable, that is to say worthy of adoration.”

The miracle of “Jules and Jim” is that it manages to frame seriousness within a dazzling depiction of life’s evanescence. “Jules and Jim” is a joyous film that is thrilling to watch. Jeanne Moreau commented on the film thirty years after she played the role of Catherine: “We were perfectly in synch. You can almost touch the intensity and fluidity of life. We were not acting, just being our selves. It was such a joyous time. Light and grave.”

“Jules and Jim” opens with a spirited narration that tells of two young men, one French, one Austrian, who meet in Paris before World War I and become lifelong friends. “They taught each other their languages, they translated poetry.” The characters take their ideas of life from books, and writing books is what inspires them most. Jules (Oskar Werner) is a shy but charming Austrian. He is still learning the ropes in Paris. Jim (Henri Serre) is a tall, lanky Frenchman who has a way with the ladies. The two carry on a constant, animated conversation about their two great interests in life: writing and women.

Truffaut uses footage from silent movies to capture life in Paris before the war. When placed next to the sun-dappled scenes in Paris shot by the cinematographer Raoul Coutard, the found footage conveys the feeling of historical Paris. Truffaut said he wanted his film to resemble an “old photo album.”

Truffaut’s camera work is so fluid it leaves us overwhelmed with life’s possibilities. At one point, the camera follows a young woman in a bar, circles the room, and then winds up watching Jules draw another girl’s face on the surface of a round table. Throughout the film, George Delerue’s exquisite music is a crucial part of the film’s atmosphere.

Jules is looking for a girlfriend but those he dates are too silent or too talkative or otherwise flawed. Jules decides to try a professional but that’s not the answer either. Truffaut sums up Jules’ disappointment with professionals with a shot of a woman’s ankle with a wristwatch around it. After giving up on professionals, Jules believes he has found his ideal girl in Therese. Therese is the girl who creates the famous moment in the film of the “steam engine,” popping the lighted end of a cigarette into her mouth and blowing smoke out the other end. When Jules realizes that Therese is not his perfect mate, his explanation to Jim is revealing, “She was both mother and daughter to me.”

The two friends do not truly come alive until they meet the magnificent Catherine (Jeanne Moreau). When Catherine enters their lives, Jules and Jim want to continue their close friendship amid the excitement of Catherine’s presence. They are both in love with her. A famous shot shows the three of them in a rented cottage at the beach, talking as they lean out their separate windows.

Jules takes Catherine to Austria where they are married. The war intervenes and separates the two friends. As members of enemy armies, they worry that one might shoot the other. After the war, Jim visits Jules and Catherine in their cottage on the Reine. They have a daughter, Sabine, but their marriage is unhappy. Jules confides that Catherine has run away and had affairs but he stays with her because he loves her and understands her. Jules encourages Jim’s interest in Catherine, “If you love her,” Jules tells him, “don’t think me an obstacle.” Catherine asks Jim to move into the house. “Careful, Jim, careful for both of you,” Jules says.

Although “Jules and Jim” is named for the men, the center of the film is Catherine, a creature both timeless (Jules and Jim first see her face reflected in a Greek statue) and forever changing. She claims for herself the male freedoms that women have been traditionally denied. She often dresses herself in men’s clothing. The men abandon their philosophical debates to follow her as she instigates bicycle rides, foot races, and general mayhem. Wherever she leads, they follow.

For Catherine capriciousness is a matter of principle. When Jim says he understands her, she replies, “I don’t want to be understood.” Catherine, however, cannot face the full consequences of her freedom to live life on her terms. She can leave men, but if they leave her she feels abandoned and desolate.

At the end of the film, when Catherine can no longer be sure of Jim’s love, she chooses death and calls on Jules to witness her choice, a final demonstration of her feminine power. The original of Catherine was still alive when the film was released. Her real name was Helen Hessel. She attended the premiere and then confessed, “I am the girl who leaped into the Seine out of spite, who married dear, generous Jules, and who, yes, shot Jim.” (In the film, Catherine merely points a pistol at Jim.)

“Jules and Jim” stands alongside Godard’s “Breathless” as one of the definitive films of the French New Wave. The miracle of “Jules and Jim” is that it manages to frame seriousness within a thrilling portrayal of the joy of living. Truffaut put it this way, “I begin a film believing it will be amusing and along the way I notice that only sadness can save it.”

Regarding the novel “Jules and Jim” by Henri-Pierre Roche

I watched “Jules and Jim” in college when I was twenty. I remember being delighted. I watched “Jules and Jim” again when I was seventy and I was even more delighted. I learned that Truffaut said he was “overwhelmed” upon reading the novel “Jules and Jim” for the first time. This was reason enough for me to read the novel in order to see for myself what the novel was like and whether it was possibly even better than the movie.

It is interesting to debate which is the higher art, literature or movies. I tend to come down on the side of movies. Movies have images, sounds, music, and words. Books only have words. I nodded in agreement when Stanley Kubrick said, “The screen is a magic medium. It has such power that it can retain interest as it conveys emotions that no other art form can hope to tackle.”

Three times, while writing this book, I was so swept away by a movie that I decided to read the book upon which the movie was based. In addition to “Jules and Jim,” I also read the novels “My Brilliant Career and “Remains of the Day.” Each time, after reading the book, my conclusion was the same. The movie was magnificent but the book was even better! In my mind’s eye, I pictured the characters in the movie while I was reading. As I read, Jules was still Jules, Jim was still Jim, and Catherine was still as capricious as ever. The book, though, was overflowing with words and these words provided delicious detail missing from the movie. I found myself in love with the characters and their story and I can only report that I felt “overwhelmed” with emotion while reading “Jules and Jim!”

The sentences in “Jules and Jim” were short and simple, just as Truffaut describes them in his afterword to the novel:

“From the very first lines, I fell in love with Henri-Pierre Roche’s prose. At that time, my favorite writer was Jean Cocteau for his quickfire sentences, their perceptible dryness and the precision of his images. I was discovering, in Henri-Pierre Roche, a writer who seemed to me to be stronger than Cocteau, for he achieved the same kind of poetic prose using a less extensive vocabulary, and making ultra-short sentences from everyday words…Jules and Jim is a novel about love in telegraphic style, written by a poet who has forced himself to forget his culture and to string words and thoughts together in the way a laconic, down-to-earth peasant would do.”

Truffaut’s description of Roche’s prose style reminds me of similar remarks by Henry Miller regarding the simple, direct style of the incomparable French novelist Jean Giono who also used simple sentences to write prose that pierces the heart like poetry. Here is a passage from the novel “Jules and Jim” which I hope will convince you to read Henri-Pierre Roche’s dazzling novel:

“Gertrude gave herself to Jim. She came to see him in the evening once or twice every week. She was a generous full blooded creature. When they were not making love she told him all about her life, which she looked upon as a perpetual game against God; she was always the loser. A whole gamut of Northern temperament and emotions, such as he had never met before, was revealed to Jim. She told him about her problems. Neither of them slept when they were together, though Jim did sometimes feel his eyelids flicker. She liked his way of listening but never gave him her close attention.

Our Jules is a charming man, she said. He understands women better than any man I know, and yet, when it comes to taking us, he loves us too much and not enough. Sometimes he’s witty, sometimes he wants us; either way he always chooses the wrong moment. I’ve done my best to help him but it’s no good. He turns Lucy into a patient idol and worships her. Jules is a discoverer and a poet, but as a husband he’d be too gentle, one would always be in his debt.”

You simply must read “Jules and Jim!” Roche’s novel is sublimely beautiful, extraordinarily wise, and unbelievably entertaining!

Francois Truffaut

Francois Truffaut, the director of “400 Blows,” is a central figure in the French New Wave. His youth was troubled and full of drama. He was brought up by his maternal grandmother until he was ten years old. It was only when she died that he went to live with his parents.

Truffaut’s new life with his parents was difficult. His mother found his presence in their cramped apartment annoying and he was forced to sit quietly reading a book for fear of disturbing her. He would often stay with friends and try to be out of the house as much as possible.

Truffaut found refuge from his troubled home life at the movies. As he got older, he skipped school frequently, sneaking into theaters because he didn’t have enough money for admission. The movies became both a refuge and an education. At the age of fourteen, after being expelled from school, he decided to be self educated. His self-assigned curriculum was to watch three movies a day and read three books a week.

There were over four hundred movie theaters in post-war Paris. Two hundred of these were near the Truffaut residence. By the time he was a teenager, Truffaut was a serious student of cinema. He impressed his friends with his knowledge of movies and was looked upon as a “living cinematheque.” Truffaut started a movie club. He called it Cercle Cinemane (the Movie Mania Club). Around this time, Truffaut met Andre Bazin. Bazin would have a great impact on Truffaut’s professional and personal life. Bazin was a well known critic and the head of another film society. He became a friend and mentor to Truffaut.

Truffaut was caught stealing a typewriter from his stepfather’s office and forging pay slips in a desperate effort to keep the Cercle Cinemane going. His stepfather was enraged and forced Truffaut to sign a confession. He then took him to a police station where he demanded that Truffaut be placed in a reform school for delinquents.

Truffaut spent three months in the Paris Observation Centre for Minors. Most of the time was spent in solitary confinement. The director of the Centre grew fond of Truffaut, however, and brought him a regular supply of movie magazines. Truffaut was released as a result of the efforts of his friend Andre Bazin and went to work as Bazin’s personal assistant.

Truffaut attended meetings at Bazin’s film society. The society was sponsored by such established figures as Jean Cocteau, Robert Bresson, and Rene Clement. The society became the center of movie life in Paris.

Its screenings were packed and important filmmakers like Roberto Rossellini and Orson Welles came to present their work. Truffaut was now part of a group of film lovers. He became friends with Jean-Luc Godard and Eric Rohmer.

Truffaut set himself the goal of writing for Cahiers du cinema, a magazine founded by Andre Bazin. A long article he wrote entitled “A Certain Tendency in French Cinema” was published in the magazine and established his reputation as a movie critic. His article had an immediate and widespread impact.

Truffaut’s criticism was directed at the most esteemed French directors and screenwriters of the day. They were responsible for what Truffaut labeled the “tradition of quality” (for Truffaut this was not praise). Truffaut declared their movies stilted and unnatural. They were marred by “literary” dialogue, overuse of studio sets rather than actual locations, and excessively polished photography.

Truffaut proclaimed, “The films of tomorrow will not be directed by the civil servants of the camera, but by artists for whom shooting a film constitutes a wonderful and thrilling adventure.” Truffaut would soon have the opportunity to put his theories into practice. His films would reflect all his formative experiences: a trying home life, a rough and tumble childhood, a constant search for love, and, above all, a deep and abiding love of movies.