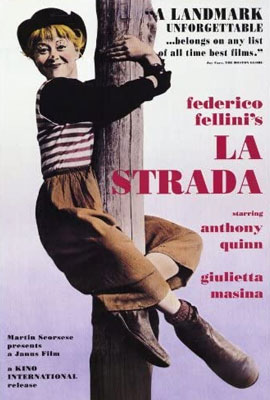

(1954)

directed by Federico Fellini

“La Strada” is a bridge between the post-war Italian neorealism which shaped Fellini’s early work and the autobiographical masterpieces that followed. Roger Ebert, the well known film critic, explains the importance of “La Strada” in Fellini’s career:

“It is fashionable to call ‘La Strada’ his best work, to see the rest of his career as a long slide into self-indulgence. I don’t see it that way. I think ‘La Strada’ is part of a process of discovery that led to the masterpieces ‘La Dolce Vita’ (1960), ‘8 1/2’ (1963) and ‘Amarcord’ (1974), and to the bewitching films he made in between, like ‘Juliet of the Spirits’ (1965) and ‘Fellini’s Roma’ (1972).”

“La Strada” is set in a timeless landscape of windswept beaches, tattered carnivals, and lonely piazzas. It is an existentialist fable with similarities to “Waiting for Godot.” Fellini cast his wife, Giulietta Masina, as the childlike Gelsomina and the strong featured, charismatic Anthony Quinn as the brutish Zampano. Zampano tours Italy in a decrepit caravan pulled by a motorcycle.

Zampano purchases the simple minded Gelsomina, the daughter of an impoverished widow, to serve as an assistant for his strongman act. Zampano teaches Gelsomina drum roll and clown routines for his act and shows her how to cook and clean the cart that serves as their home. Gelsomina delights in fantasy and spontaneous performance. In one scene, she entertains the guests at an outdoor wedding with an impromptu dance.

Zampano forces Gelsomina to sleep with him. After their first night together, Gelsomina awakens to tears. Her expressive eyes seem to hold all the sadness of the world.

In a provincial town, Gelsomina is awestruck by the performance of the Fool, a trapeze artist who works high above the city street. Fellini turns again and again to the image of a figure suspended between earth and sky. In “La Strada,” the Fool is that figure. Fellini would rework this image until the end of his life.

Zampano signs up with the traveling circus where the Fool is employed. Gelsomina imagines a life with the Fool away from the hardships of her life with Zampano but the Fool convinces her to stay with Zampano, despite his selfish brutality, because, “Everything serves a purpose, even the stones.”

The Fool makes fun of Zampano, who attacks him in an explosion of rage and is jailed. Zampano’s rage returns and he beats the Fool to death by the roadside to Gelsomina’s horrified cries of “No!” Gelsomina goes mad and her constant whimpering goads Zampano’s conscience. Zampano cruelly abandons Gelsomina high in the snow-covered mountains.

Zampano’s tragedy is that he loves Gelsomina but doesn’t know that he loves her. The film ends when Zampano, who has by chance learned that Gelsomina died of a broken heart, returns to the desolate seashore and wades into the sea. There he realizes how truly alone he is.

The music of Nino Rota is crucial to the film’s emotional power and is one of the most distinctive film scores ever written. With his violin, the Fool contributes an exquisite musical theme which evokes the folk traditions of the countryside. The score merges circus music and popular songs with the sounds of accordions.

“La Strada” won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. Fellini later said that “La Strada” was “a catalogue of my entire mythological world, a dangerous representation of my identity that was undertaken with no precedent whatsoever.”

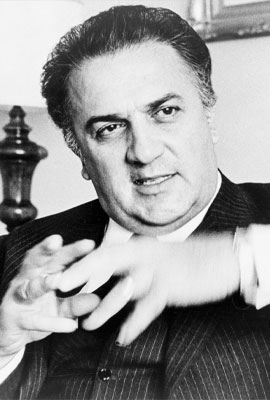

Federico Fellini

Federico Fellini, the director of “Nights of Cabiria,” is known for films that blend fantasy and earthiness. Fellini turns again and again to certain images: the circus, parades, the seashore, and a figure suspended between earth and sky. You will find journeys, processions, clowns, freaks, and the melancholy of a field at dawn after the circus has left. Fellini would rework these images until the end of his life.

In childhood, Fellini discovered the world of Grand Guignol, the circus with Pierino the Clown. Later, after he became a famous filmmaker, Fellini said, “The clown is always the caricature of a well-established, ordered, peaceful society. But today all is temporary, disordered, grotesque. All the world plays a clown now.”

Before his career as a filmmaker, Fellini achieved success while employed at Marc’Aurelio, a very popular humor magazine. Fellini met his future wife, Giulietta Masina, in a studio office. Masina was already famous for her musical-comedy broadcasts during the second World War. Their partnership was crucial. Working together they created timeless, unforgettable characters, and truly extraordinary movies.

Fellini’s overriding concern with developing a poetic form of cinema was outlined in an interview with The New Yorker journalist Lillian Ross, “I am trying to free my work from certain constrictions, a story with a beginning, a development, an ending. It should be more like a poem with metre and cadence.”

Fellini is recognized as one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers of all time. He was nominated for twelve Academy Awards and won four in the category of Best Foreign Language Film, the most for any director in the history of the Academy.