(1950)

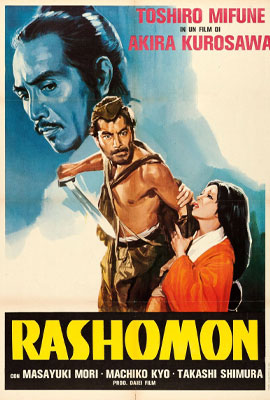

directed by Akira Kurosawa

“Rashoman” takes place in eleventh century Japan during a time of civil war. Two men, a priest and a woodcutter, take shelter from a fierce rain storm in the ruins of Kyoto’s Rashoman gate. A third man, a peasant, joins them to escape the rain and engages the first two in conversation. They tell him that a notorious bandit is on trial for murdering a samurai and raping his wife in a remote forest.

The woodcutter speaks first. He says, “I just don’t understand.” The woodcutter has just heard each of the participants (the bandit, the wife, and the husband’s spirit speaking through a medium) describe the same events. Each story is different and all three claim to be the killer. Because each story is different, and because the stories all describe the same event, we know they cannot all be true.

Even when witnesses try to tell the truth, their testimonies may still be untruthful because as Kurosawa observes in his autobiography, “Human beings are unable to be honest with themselves about themselves.” The characters, Mr. Kurosawa said, have a “sinful need for flattering falsehood” and “cannot survive without lies to make them feel they are better people than they really are.”

The woodcutter’s opening journey into the forest suggests he is traveling into another realm. At times, the cinematographer, the famed Kazuo Miyagawa, shoots through the forest canopy directly into the sun as his camera moves through the forest. The streaks of light behind the blur of limbs remind us what it is like to move swiftly through a forest. Down below, the flickering shadows from the leaves overhead cause the characters to practically disappear into the forest floor. In a series of shadowy flashbacks, we can see for ourselves what each participant says they saw. Because we see the events in flashback, we assume they reflect the truth. The stories all disagree, however, and it appears that the participants are not lying for their own benefit because each claims to be the killer. Are truth, memory, and the past merely fictions?

The woodcutter testifies that he found the body of the samurai. Later, he admits that his testimony was false. The woodcutter now claims to have seen the bandit begging the woman to run away with him after the rape. The wife demands that the two men duel for her hand. The men duel and the samurai is killed. The bandit’s story is more complicated, but roughly agrees with the woodcutter’s version. He claims he tricked the samurai, tied him up, raped the wife in front of her husband, and then, at the wife’s request, dueled the husband and emerged victorious. The wife, on the other hand, claims her husband shunned her for being raped and that she killed her husband in retaliation. Finally, the husband’s spirit testifies through a medium that his wife agreed to run away with the bandit after the rape but only if the bandit first killed her husband. The bandit refused and out of grief the husband killed himself with his wife’s dagger.

The peasant, after hearing all these different accounts, sums things up by saying, “Don’t worry about it, it isn’t as though men were reasonable.” Suddenly, the three men at the gate hear an abandoned baby crying. The peasant decides to steal the child’s clothes to sell for food. The priest and woodcutter are appalled by his heartlessness. The woodcutter takes the child in his arms and vows to take care of the child. The rain suddenly stops and the sun breaks through the clouds.

Among the film’s influences were a pair of catastrophes that Kurosawa experienced first hand: the great Tokyo earthquake and the firebombing of Tokyo during the second World War. Kurosawa was only thirteen when the earthquake occurred. His older brother insisted they walk through the ruins and view the corpses in order to overcome fear by staring reality in the face.

“Rashoman” is an unflinching modernist masterpiece that questions the very existence of truth. The truth about what happened in the forest is never revealed. For Kurosawa, the inability of the witnesses to accurately recall the violent events in the forest suggests that they may have fallen into a horrifying black hole in human consciousness in which the truth disappears entirely. The kindness of the woodcutter at the end of the film barely softens this dark message.

“Rashoman” was an international sensation. Audiences had never seen anything like it. “Rashoman” won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, effectively opening the world of Japanese cinema to the west. It also won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. It set box office records for a subtitled film. The film’s title quickly entered the English language and became shorthand for the relativity of truth.