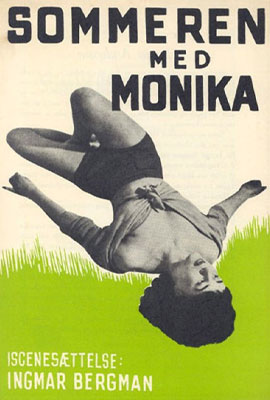

(1953)

directed by Ingmar Bergman

“Summer with Monika” is a portrait of young love. We are present when Monika (Harriet Andersson) and Harry (Lars Ekborg) first meet across adjacent tables at a cafe. Harry’s clumsy attempts to light Monika’s cigarette are not an impediment to their sudden liking for one another. Romance offers a very welcome diversion to working life in stifling, industrial Stockholm.

“Summer With Monika” is an important film in Bergman’s career because it marks a shift toward making female characters the focus of his films. The central importance of female characters in his films would continue for the rest of Bergman’s career.

Monika’s dreams of escape and her refusal to conform are central to the film’s story. Just twenty years old at the time of filming, Harriet Andersson portrays a young woman who embraces her sexuality. Monika dreams of escaping her hellish home life with an abusive, alcoholic father.

Monika’s dreams of escape are partly motivated by her love of movies. Early in the film, after a night out at the movies with Harry, Monika looks at expensive clothing in a shop window and fantasizes about the elegant lives of movie stars. When she tells Harry, “You may kiss me now,” her words echo the words in the movie they have just seen.

In Andersson, we see the arrival of a new kind of movie star, one with a natural beauty that is the opposite of the usual Hollywood glamour. Monika’s unshaven armpits, lack of make-up, and rebellious behavior especially influenced the portrayal of women in the French New Wave. Andersson was heralded as the New Woman in European cinema alongside Jean Seberg, Jeanne Moreau, and Emmanuelle Riva.

“Summer With Monika” is based on the seasons. Young lovers meet in spring. They share a blissful summer together. They are disillusioned in autumn. They part in winter.

The journeys to and from the island are especially resonant. The beautiful sequences along the waterways of Stockholm capture the exhilaration of the lovers’ escape and their heartbroken return. The chiming of city clocks marks the moment of their departure. Bergman returns to the images and sounds of clocks again and again in his films.

“Summer With Monika” was shot by the cinematographer Gunnar Fischer utilizing a formal style. The black and white cinematography has a lovely, understated beauty. The island sequences celebrate open spaces surrounded by the sea. The images of Monika at dawn on their first morning on the island are breathtaking. She scampers barefoot in white shorts across the rocks. Later, there is a shot across the bay in which she is hidden in the tall waterside grasses. When Monika says “I want summer to go on just like this,” she advocates cherishing the moment. The director Jean-Luc Godard, discussing “Summer With Monika,” said that Bergman’s camera “seeks only one thing, to seize the present moment at its most fugitive and delve deep into it to give it the quality of eternity.”

Once Monika becomes pregnant, the heavy weight of responsibility bears down on the young lovers. Harry wants to complete his education, find a good job, and enjoy the good life with his wife and child. Monika sees Harry’s striving as just another trap and refuses to go along with his plans. Her decision to opt instead for an immediately available, less emotionally demanding man suggests that betrayal by the woman is inevitable when an earthy, spontaneous woman is matched with an emotionally sensitive, intellectual man. We see this same dynamic at work in Woody Allen’s film “Whatever Works,” a film that also suggests that a relationship between mismatched partners simply does not work. I have read that Woody Allen stood in line overnight to be among the first to see “Summer With Monika” when it first arrived in the United States.

The most extraordinary moment in “Summer With Monika” occurs near the end of the film. Monika sits in a cafe with a man and, as music rises from the jukebox, turns to stare directly into the camera. Such a shot was practically unheard of at the time. Monika’s long stare into the camera expresses the primacy of the human face and reveals, in a single glance, her selfishness, her self-destructiveness, her defiance, and what Samuel Beckett called “that desert of loneliness and recrimination that men call love.”

Godard and Truffaut were both transfixed by Monika’s defiant gaze and this shot inspired the closing shots of both Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless” and Francois Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows.”

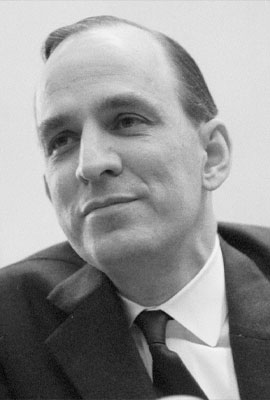

Ingmar Bergman

Ingmar Bergman, the director of “Summer With Monika,” is surely the twentieth century’s most important art film director. Between 1946 and 1983 Bergman wrote and directed such renowned classics as “The Seventh Seal,” “Summer With Monika,” “Wild Strawberries,” “Smiles of a Summer Night,” “The Virgin Spring,” “Persona,” “Cries and Whispers,” and “Fanny and Alexander,” to mention only the most famous of his films. If you wish to experience what the medium of film is truly capable of, Bergman’s extraordinary films are surely the place to start.

Bergman was the son of a Lutheran pastor and often remarked on the importance of his childhood background on the development of his ideas. Even when his characters’ challenges are not overtly religious, his characters are always engaged in a rigorous examination of their actions and motives.

Bergman attended Stockholm University where he studied art, history, and literature. There he became passionately involved in the theater and began writing and acting in plays and directing student productions. From there, he went on to become a trainee director at the Master Olofsgarden Theater. He was given his first full-time job as director of Helsingborg’s municipal theater. There he met Carl-Anders Dymling, the head of the Svensk Filmindustri. Bergman received a commission to write an original screenplay for the film “Frenzy.” The film was directed by Alf Sjoberg, then Sweden’s leading film director. “Frenzy” was an enormous success both at home and internationally and Bergman’s reputation was established.

Bergman’s films reflect his work in theater. The kindly theater manager in “Fanny and Alexander” seems to speak for Bergman when he reflects on his career, “My only talent, if you can call it that in my case, is that I love this little world inside the thick walls of this playhouse, and I’m fond of the people who work in this little world. Outside is the big world, and sometimes the little world succeeds in reflecting the big one so that we understand it better.” Bergman began to gather around him, in both his film and stage productions, a faithful ensemble of actors, including Harriet Andersson, Bibi Andersson, Gunnar Bjornstrand, Erland Josephson, Ingrid Thulin, Liv Ullmann, and Max von Sydow, all of whom he worked with regularly.

Bergman’s films are especially noteworthy because they often revolve around female characters. When Harriet Andersson turns and stares defiantly into the camera in “Summer With Monika,” she stakes her claim to her place in the world. Women have a crucial role in Bergman’s films and reflect his passionate love of women.

Anthony Lane, paying homage to Bergman’s films in the “New Yorker,” reflects on the legacy of Bergman’s films:

“Bergman’s movies cannot and must not be mistaken for abstract ruminations, let alone cautiously balanced debates. They are violently, ecstatically open to the evidence of the senses; you can feel every particle of experience drumming on the characters like rain. The parents who cradle their dead child in a forest, at the finale of “The Virgin Spring,” are joined and bowed in grief, but because we regard them from overhead, in a tableau of lamentation, and because the light that floods the glade is beatific, the tone is calmly and peculiarly blessed, as is proved, shortly afterward, when they raise her body and water flows from the earth on which she lay. The title, we now realize, refers to a miracle.”

Ingmar Bergman is universally recognized as one of the most important figures in cinema. His films address the attempt to discover one’s personality by the removal of masks to find the real human being underneath. The idea of the director and actor as creator and magician recurs throughout Bergman’s work. In Bergman, these themes combine to create an artist of great power and originality.