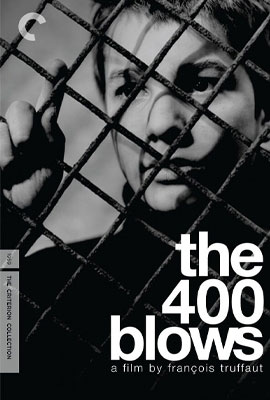

(1959)

directed by Francois Truffaut

Truffaut said again and again that movies had saved his life. He said that movies had given him something to live for during his troubled youth. With the encouragement of his mentor and close friend Andre Bazin, he first became a movie critic and then a filmmaker. “The 400 Blows” was Truffaut’s first feature film and was completed when he was twenty-seven years old. Andre Bazin died while “The 400 Blows” was being filmed. Truffaut dedicated his film “To the memory of Andre Bazin.”

The film is based on Truffaut’s childhood. The film tells the story of twelve year old Antoine Doinel, his unhappy home life, his adventures skipping school, and his time in reform school. Jean-Pierre Leaud was chosen for the part of Antoine because of his close physical resemblance to Truffaut at the same age. Jean-Pierre Leaud plays the part of Antoine with a solemn expressiveness that suggests a sensitive spirit and that reminds us that one’s childhood can cast a long shadow. The actor and director returned to the character of Antoine in three more films, “Stolen Kisses,” “Bed and Board,” and “Love on the Run.”

“The 400 Blows” is one of the most sensitive, deeply moving films ever made about childhood. Antoine is living with his mother and stepfather in a crowded apartment where they always seem to be in each other’s way. The mother is distracted by financial worries, by her son, and by an affair she is having with a man at work. The stepfather is reasonable enough, but is not deeply attached to Antoine. The parents are often away from home.

The phrase “400 Blows” is idiom for “hell raiser.” At school Antoine is seen as a troublemaker. Made to stand in the corner, he expresses his feelings by writing on the wall. For homework, the teacher orders him to complete a grammatical exercise based on the sentences he has written on the wall. His homework is interrupted. Rather than return to school the next day with incomplete homework, he decides to skip school. His excuse is that he was sick. After his next absence, he says his mother has died. When she turns up at his school, Antoine loses all credibility.

When Antoine is assigned to write an essay on an important event in his life, he describes “the death of my grandfather’’ in language which is a close paraphrase of Balzac. This is seen by his teacher as plagiarism rather than as homage to a great writer. This results in even more punishment. Antoine continues to skip school and spends a lot of time sneaking into movies. We see Antoine’s serious face looking up at the movie screen and are reminded that the young Truffaut escaped to the movies whenever he could. When Antoine and a friend emerge from a movie, Antoine steals one of the movie posters in the lobby.

The beautiful black and white cinematography captures a cold season in Paris. Antoine usually has the collar of his jacket turned up to protect him from the cold and wind. Truffaut invested a large part of the film’s modest budget to hire Henri Decae, one of the best cinematographers working at the time.

In the movie’s final sequence, Antoine escapes from reform school and makes his way to a vast, lonely seashore. He crosses the beach for his first glimpse of the ocean. The camera travels with him until he reaches the water’s edge. Antoine then turns to face the camera. He stands between the land and the sea and between the past and the future. The film ends with Antoine looking directly into the camera. A moment in time is captured by the camera and leaves us feeling completely overwhelmed. “The 400 Blows” won the Best Director Award at the Cannes Film Festival.

Francois Truffaut

Francois Truffaut, the director of “400 Blows,” is a central figure in the French New Wave. His youth was troubled and full of drama. He was brought up by his maternal grandmother until he was ten years old. It was only when she died that he went to live with his parents.

Truffaut’s new life with his parents was difficult. His mother found his presence in their cramped apartment annoying and he was forced to sit quietly reading a book for fear of disturbing her. He would often stay with friends and try to be out of the house as much as possible.

Truffaut found refuge from his troubled home life at the movies. As he got older, he skipped school frequently, sneaking into theaters because he didn’t have enough money for admission. The movies became both a refuge and an education. At the age of fourteen, after being expelled from school, he decided to be self educated. His self-assigned curriculum was to watch three movies a day and read three books a week.

There were over four hundred movie theaters in post-war Paris. Two hundred of these were near the Truffaut residence. By the time he was a teenager, Truffaut was a serious student of cinema. He impressed his friends with his knowledge of movies and was looked upon as a “living cinematheque.” Truffaut started a movie club. He called it Cercle Cinemane (the Movie Mania Club). Around this time, Truffaut met Andre Bazin. Bazin would have a great impact on Truffaut’s professional and personal life. Bazin was a well known critic and the head of another film society. He became a friend and mentor to Truffaut.

Truffaut was caught stealing a typewriter from his stepfather’s office and forging pay slips in a desperate effort to keep the Cercle Cinemane going. His stepfather was enraged and forced Truffaut to sign a confession. He then took him to a police station where he demanded that Truffaut be placed in a reform school for delinquents.

Truffaut spent three months in the Paris Observation Centre for Minors. Most of the time was spent in solitary confinement. The director of the Centre grew fond of Truffaut, however, and brought him a regular supply of movie magazines. Truffaut was released as a result of the efforts of his friend Andre Bazin and went to work as Bazin’s personal assistant.

Truffaut attended meetings at Bazin’s film society. The society was sponsored by such established figures as Jean Cocteau, Robert Bresson, and Rene Clement. The society became the center of movie life in Paris.

Its screenings were packed and important filmmakers like Roberto Rossellini and Orson Welles came to present their work. Truffaut was now part of a group of film lovers. He became friends with Jean-Luc Godard and Eric Rohmer.

Truffaut set himself the goal of writing for Cahiers du cinema, a magazine founded by Andre Bazin. A long article he wrote entitled “A Certain Tendency in French Cinema” was published in the magazine and established his reputation as a movie critic. His article had an immediate and widespread impact.

Truffaut’s criticism was directed at the most esteemed French directors and screenwriters of the day. They were responsible for what Truffaut labeled the “tradition of quality” (for Truffaut this was not praise). Truffaut declared their movies stilted and unnatural. They were marred by “literary” dialogue, overuse of studio sets rather than actual locations, and excessively polished photography.

Truffaut proclaimed, “The films of tomorrow will not be directed by the civil servants of the camera, but by artists for whom shooting a film constitutes a wonderful and thrilling adventure.” Truffaut would soon have the opportunity to put his theories into practice. His films would reflect all his formative experiences: a trying home life, a rough and tumble childhood, a constant search for love, and, above all, a deep and abiding love of movies.